Are Mongolia’s SOEs a Burden or a Backbone?

Sep 30, 2025

Tselmeg E.

Few institutions in Mongolia’s economy spark as much debate as its state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Officially, there are 109, though this number shrinks to 67 once holdings are consolidated, with the Erdenes Mongol Group alone folding 16 mining companies under its umbrella. In practice, however, just a handful of mining giants — Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi JSC, Erdenet Mining Corporation, and Erdenes Mongol — dominate the sector, generating the lion’s share of revenues and shaping the country’s economic fortunes.

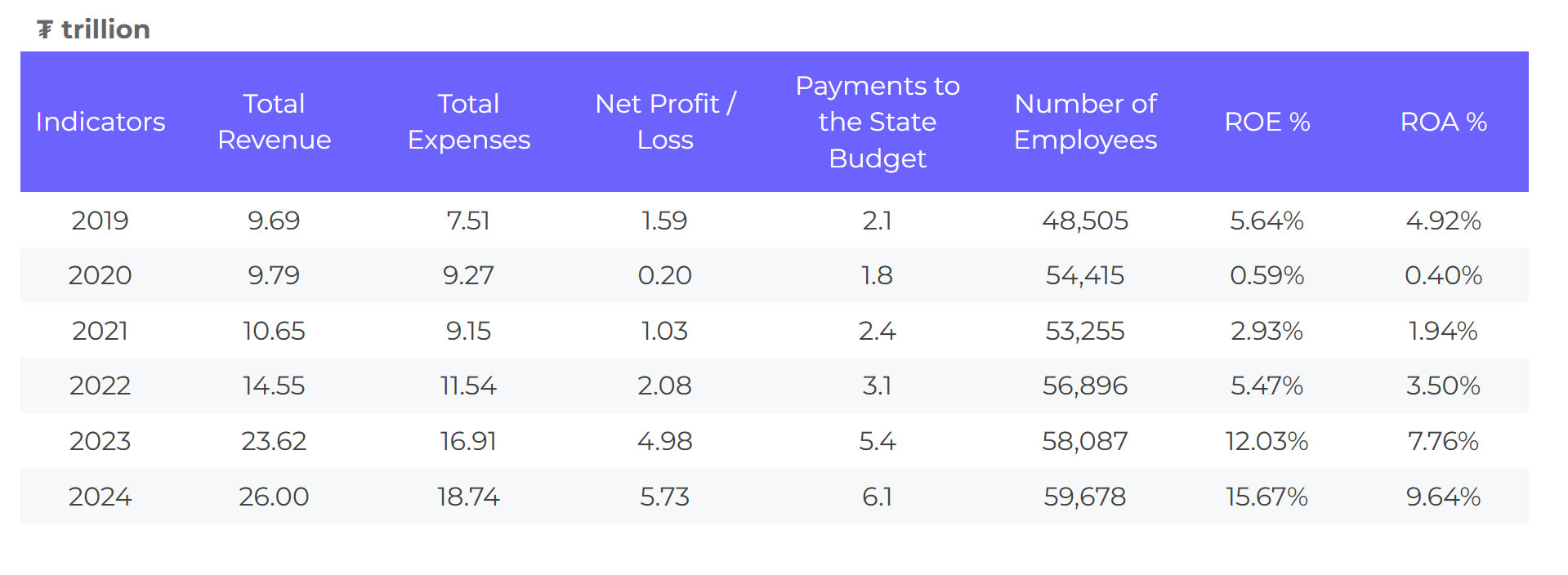

If we look at the numbers, SOEs look indispensable — ₮26 trillion in revenue and ₮5.7 trillion in profit in 2024, with the Erdenes Mongol Group providing nearly two-thirds of the total.

Table 1. Performance of SOEs (2019-2024)

Yet behind these headline figures lies a fragile reality. Nearly one in four SOEs still runs at a loss, draining public funds through bloated costs, subsidized services, and chronic inefficiencies.

Instead of driving growth, many have become fiscal burdens, dependent on state support to survive. Weak corporate governance and persistent political interference compound the problem: boards remain dominated by government officials rather than independent professionals, fueling patronage, short-term political cycles, and corruption. The notorious coal export scandal revealed just how vulnerable the system is when ownership, regulation, and management are blurred, leaving SOEs more of a liability than an asset.

“The costs are not just fiscal—they are strategic”

The opportunity cost is immense, extending beyond fiscal losses to strategic setbacks. By channeling capital into inefficient enterprises, Mongolia risks missing the global critical minerals boom that could otherwise secure long-term prosperity. Aging infrastructure and monopolized services crowd out private competition, reducing innovation and discouraging foreign investors.

However, it would be misleading to dismiss SOEs only as fiscal drains. They remain central to Mongolia’s economy — controlling strategic sectors such as mining and energy, subsidizing essential services like power and transport, and channeling resource revenues into the state budget. Their sheer weight makes them too important to ignore, but also too risky to leave as is. Without change, the very institutions that sustain Mongolia’s economy could continue to undermine its growth.

This contradiction lies at the heart of Mongolia’s dilemma: today, SOEs resemble more of a burden than a backbone — draining resources and eroding trust — yet they hold the potential to become true pillars of the economy if transformed into commercially viable, transparent, and professionally governed enterprises capable of delivering both profits and public value.

“The IPO alone does not guarantee better SOE performance.”

The government’s 2025–2028 reform roadmap—focused on domestic IPOs, restructuring, and stronger governance—could be a turning point. But the question remains: do IPOs on the domestic stock exchanges truly deliver better performance? Mongolia has already listed several SOEs in the past, yet their results have been mixed, with little to no evidence that listing alone improves efficiency or governance.

The real significance of the roadmap may therefore depend not only on bringing companies to market but on whether it genuinely opens the door to broader opportunities — such as dual listings, bringing strategic investors via private placements, or even a national investment fund — that can reshape incentives and ensure lasting impact.

To achieve this, Mongolia must go beyond announcements and commit to structural change. First, governance reform must precede market reform. Boards should be restructured to include independent professionals with clear fiduciary duties, insulating SOEs from political cycles and patronage. Second, transparency standards must be lifted to international levels. Adopting IFRS reporting, quarterly disclosures, and independent audits would reassure investors that SOEs are credible market players. Third, investor protections need to be strengthened. Guaranteeing dividend policies, minority shareholder rights, and dispute resolution mechanisms would build confidence both at home and abroad.

At the same time, the government should leverage strategic investors not just for capital, but for know-how. Joint ventures and private placements should prioritize partners that bring governance discipline, technical expertise, and market access. And finally, the National Investment Fund must be structured with safeguards: independent management, parliamentary oversight, and ring-fencing of assets to prevent short-term political misuse.

The fate of Mongolia’s SOEs stands at a decisive crossroads. If reforms stall, they risk becoming liabilities that drain resources, erode public trust, and hinder national progress. But if governance, transparency, and investment pathways are pursued with real commitment, SOEs could be transformed into true strategic pillars of the economy — generating profits, boosting competitiveness, and securing Mongolia’s long-term prosperity.

SOEs have two pathways going forward: Backbone or Burden — reform will determine which legacy prevails.

Read the full report: Investor’s Guide to Mongolia: State-Owned Enterprises

Loading ...